Robots Marking Robots: The AI Arms Race

Hello Detox readers, and greetings from deep within my plague house. As most parents of young children will confirm, everything is a virus and the children are always unwell; my little germ factory came home early from school on Tuesday and hasn’t been back since. My thoughts are with anyone who is also living in this strange, isolated space of no sleep and less hope. But the troubles of AI wait for no Mom, so here we are again.

Robot vs. Robot / One Hand in Your Pocket

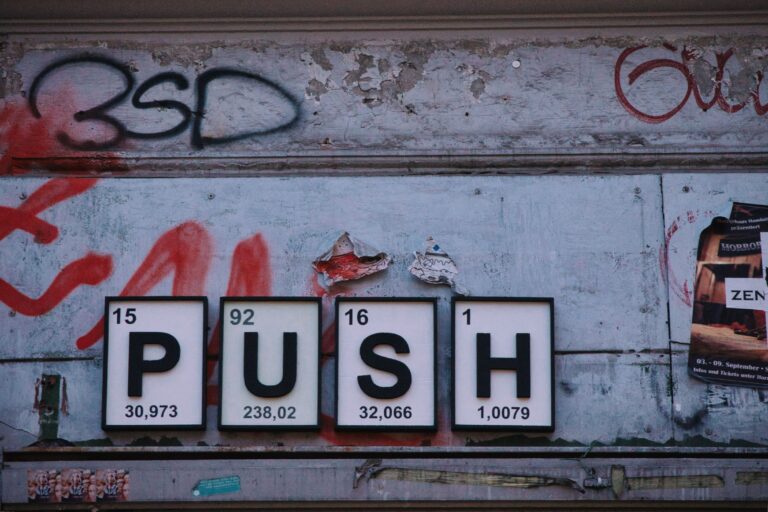

The online noise this past week has been all about that OpenAI ChatGPT detector tool. Coming soon, no doubt, to a sales pitch near you. The Classifier, as it is called (not at all an Orwellian monicker), is not actually any good at its job: it finds AI correctly about a quarter of the time, and it flags a false positive once every ten times. Seems like a problem. If you’ve mediated the conversation between a falsely-accused student and an over-zealous instructor in an academic integrity discussion, those numbers should make you very itchy. Cheating can feel really personal (I would argue inappropriately so) when you’re teaching the course and you’re the one who has to clean up the mess. And many academic integrity policies already place disproportionate burden on the accused student, and more still are antagonistic/adversarial at the core. Even when The Classifier gets better (which it will) or a more effective competitor emerges (which it will), that won’t change the fundamental core of the problem which is that we have turned essay composition into a game of cops and robbers. In the Turnitin era, the robots policed the humans; in the The Classifier era, the robots police the robots, I guess.

The other piece we can’t ignore as we look towards the burgeoning Robot War is that ChatGPT is a paid service now, and at US$20/month, not a cheap one. (The website says it will still have a free use option, but I haven’t been able to access it in well over a week.) If we compare this cost to other productivity tools, it’s still expensive: I pay US$8/month for Calendly to manage my schedule and that seemed exorbitant to me even though I use it all the time. But at $240/year, ChatGPT isn’t trying to compete with me making a weekly Doodle poll; it’s trying to compete with, like, hiring freelance writers or spending executive time writing policy. And maybe it will succeed easily there.

There are implications of a high price tag when we think through how ChatGPT intersects with our students. For one thing, a lot of those fun pedagogical plans folks have for using it in the classroom become a lot more complex once there’s a price of admission (there always was, but we tend to notice dollars missing from our pockets before we notice our data has been absconded with). More bleakly, perhaps: as we know from the arc of contract cheating, there’s never any equity in access to opportunities to cheat or in who can outsmart the detectors. Cut-and-pasters get caught by Turnitin, but those with the money to pay a contract cheating firm do not. Of course, in this case, with ChatGPT integrated into Microsoft products (already possible with a third-party add-in) our institutions will be paying for the pleasure soon enough. And then, I guess, the trajectory seems clear for the bill to come due on a site license for The Classifier.

What Are Writing Assignments For, Exactly?

So it seems clear to me that there’s a near future where ChatGPT writes the assignment and then checks the assignment and, with about 26% accuracy, announces that it wrote it. Neat. Seems dystopian, but okay. But think about all the other ways we’ve talked about this month where AI is part of the evaluative process? Indeed, one of the dreams of MOOCs was to get instructors out of the assessment role entirely to facilitate ever more learners moving through content; one such example involved instructors committing to marking 100 assessments to train an AI for essay prompts, and then only flagging the instructor thereafter if the AI assesses the essay below a certain score. (I actually don’t hate this assessment example, because it aggregates the AI assessment against self- and peer evaluations, but the point is the larger push to extract human labour from assessment as a goal.) The reality is, though, that trust is still very low in algorithmic grading processes, especially after the 2020 A-Level crisis in the UK, despite what those looking to achieve goals of scale might wish for. And those studies that are most enthusiastic about AI grading tend to be ones that decline to comment on or totally ignore issues of ethics like algorithmic biases, privacy, and so on.

Whether AI assessment works or is trusted, however, seems secondary to me to the question of why we assign essays to students in the first place. The truth is, I think often the essay form is the higher education default: when in doubt, if it can’t be an exam, assign an essay. It’s how so many of us were taught and its a choice many of us reify for lots of reasons: because essays worked for us as learners, because we don’t have time or space or material reason to think much about our practice, or because we’re required to by our roles and parameters. Of course, there are lots of alternatives to essays out there, and if there’s one thing I hope AI does disrupt it is the idea of the essay as a default assessment selection, though these ideas always require difficult conversations about labour, scale, and legitimacy.

But I return to this core question of what any assessment, in this case the essay, is for. We assign an essay allegedly to assess learning, to see what students can do with the material, and to explore the “how” of their thinking process. At least that’s why I assign essays. There’s nothing there that an AI tool can evaluate. It can check that a particular structure is used (this is why you don’t want to deviate from the five-paragraph essay on a typical standardized test) and it can look to see that key words and specific examples or references have been included. But does any of that measure learning? The essay is an artefact of the learning process only insofar as we can meaningfully assess process; we return, then, to my post from two weeks ago. An essay in a vacuum is probably not a measure of anything; paired with writing development work, reflective practice, and self-assessment, we get a bit closer to the idea that we can use the essay to assess learning.

Without those pieces, though, ChatGPT or no ChatGPT, if we’re not interested in developing the skill of writing, we should find other ways to assess.

It probably underscores my own naïveté and idealism that, in spite of everything, I believe in writing assignments as a profoundly human means of assessment. Indeed, I am very open to conversations about the ways in which ChatGPT might facilitate communication or help students unlock their capacity for writing, though that doesn’t sideline the ethical quagmire of ChatGPT, including the violences that underpin the technology. Using AI tools to make more transparent and equitable the process of writing is possible, as long as process is part of the assessment goals. And that conversation about process does take a human being. Without that, maybe robots marking robots is the inevitable end. But we walked into it knowingly — and no amount of policing, antagonism, or banning of the tools will shut this particular Pandora’s box.

Tech for Tech’s Sake

One recent meta-analysis of the research on AI student assessment notes a disjuncture between the pedagogy and the practice: in other words, the use of AI in assessment at the moment is largely limited to exploring the technology and not really asking whether learning outcomes are improved. Or in other other words, we are too busy asking whether we could, and not stopping to wonder if we should (thanks, Jeff Goldblum). This is part of the problem with the way technology is often seen as a competitive advantage or something to get ahead of rather than something to be integrated into a changing, developing conception of learning. Move fast and break things might work for tech startups (except it doesn’t), but it’s catastrophic in education to put shiny toys ahead of learning.

We need to think through the teaching and learning implications of AI, but not just of ChatGPT. We need to think through the implication of all the tools that we’ve already let inside the doors of the university, all the ways our learners are already subject to AI, all the AI tools that already surveil our workspaces.

Next week, we’ll look at the structure of the neoliberal university itself and its capacity for adaptation, change, and reform and ask: is it too late now to say sorry (with apologies to Justin Bieber)?

Years ago, I had a contract position at an institution where I was part of a program focused on writing and learning. I taught 20 students each year. I met with them in groups of 20 twice a week, and in groups of 4 once a week. And they wrote essays every few weeks. In the groups of 20 we would talk about the material being covered and explore ideas, and in the groups of 4 we would workshop essays. It was such a fun place to teach, and the students really enjoyed learning in this atmosphere as well.

But here’s the thing: this program was seen by the institution as way too expensive. With a 20/1 ratio of students to instructors, the program was always financially in jeopardy. The institution wanted more of a 400/1 ratio. And this was even though I was a contract employee (so already quite a cost saving over hiring a tenure-route employee, which they also had in this program). In addition, the program was not open to everyone. Students had to compete to be in this program, and the entry GPA requirements were pretty high, as I recall. So was this program ideal: no. In a lot of ways it needed more support than the institution was willing to give, and it was too elite.

But the program had advantages. I found that I was really able to talk about writing and thinking and connections between writing and thinking in ways that simply were not possible in larger classes. I learned my students’ individual writing styles and helped them cultivate those. And students supported each other, offering insightful critiques and helpful suggestions of each others’ work.

I suppose I am sad that more people don’t have these opportunities (I certainly didn’t as an undergrad) and that many people and institutions seem to view these models as too costly, but don’t think much about shelling out subscription fees for technology that (sort of) facilitates a 400/1 model of learning. I don’t think I really learned about writing until I was in grad school, in a 20/1 setting myself. Makes me wonder what we think undergrad is really doing.