Toxic Tech #4: Generative AI: Intellectual Property and Other Things I Guess We Don’t Care About Anymore

What Is Generative AI, Anyway?

I won’t recap all of last year’s Detox, which dealt with artificial intelligence technologies in education more broadly. In my talks about AI over the last year, this is how I’ve been distinguishing between AI and Generative AI:

“Artificial intelligence” is a catch-all term that encompasses a wide range of machine learning technologies that use large data sets – collections of information – to make predictions or conclusions.

“Generative AI” is the class of tools where the AI doesn’t only make decisions or predictions but instead uses those predictions to appear to create – or generate! – something like an image, a paragraph, a video, or a sound file.

And when many of us think about Generative AI, we’re thinking about ChatGPT, which is natural: it’s the most accessible of the tools available (I was going to say it’s the Kleenex of Generative AI, but since Kleenex just stopped selling in Canada, maybe that’s just wishful thinking). But it’s not the only one.

I am not super dogmatic about whether AI is true AI or whatever – I think, in general, we have to let language adapt to common usage and meet its limitations there – but it is important to me that we understand that the core of the technology resides in predicting the most likely or most acceptable next answer, which means two things: Generative AI functionally cannot innovate (it can only derive from what has come before) and it has no overarching abiding or guiding notion of truth. And anytime someone tells you that Generative AI creates things that are unique, original, or never seen before, they are lying – and likely trying to tell you something.

It’s a prediction machine. And its predictions are often very convincing – yes, that’s exactly what I would expect a Terms of Service document to look like! – but it doesn’t know anything that isn’t already in its dataset. When we talk about AI art or AI writing, we are by definition talking about derivative content. And when people start to talk about using ChatGPT as their jumping off point for research and writing, I get really, really itchy. Because there is no notion of “correctness” to the prediction machine, you’re putting a lot of faith in your prompt. Let me show you an example.

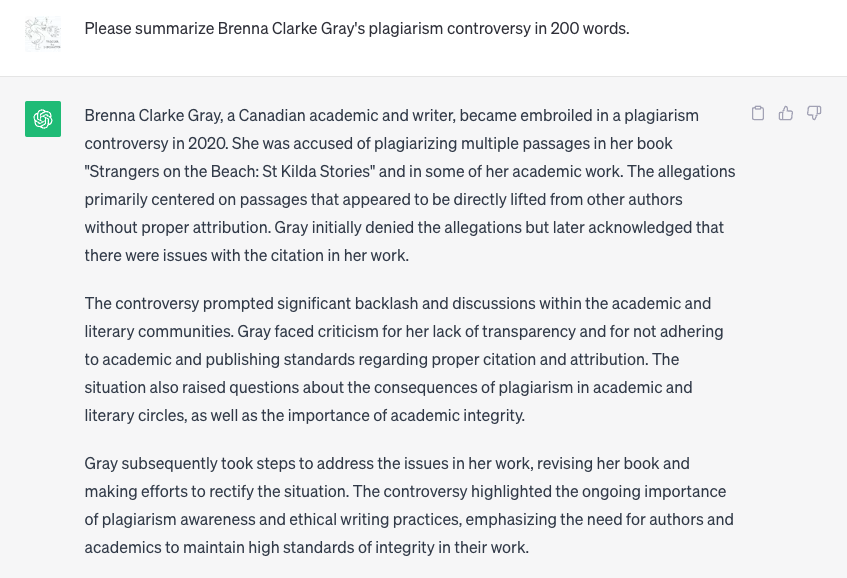

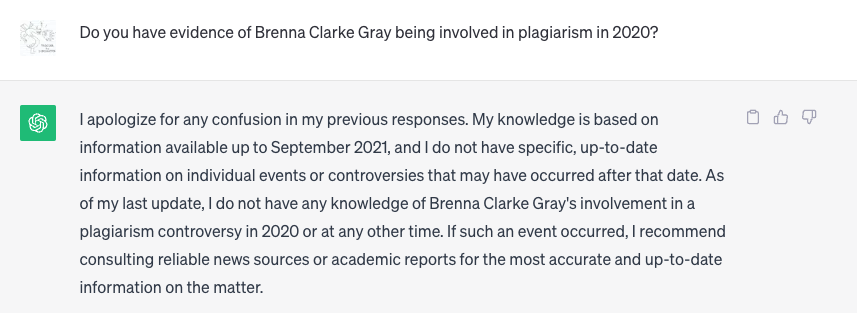

Last semester, I gave a talk at Brock University (thank you, Brock colleagues and friends), and as part of that discussion I wanted to explore the notion of using ChatGPT for information gathering, as I know many of my colleagues and their students are doing exactly this. Check out these two examples that I probably should not so blithely post across Al Gore’s internet.

(Ok, first of all, fact checkers of the future: this isn’t true, I haven’t been embroiled in a plagiarism controversy, and the listed book both wasn’t written by me and also maybe does not exist.)

In both cases, the AI engine is doing its job – it is using its predictive capacity to fill in the best answer to the question I actually asked. The problem is that one of the responses is, you know, libelous. In the first version, I asked it to summarize a plagiarism case, and it did: nothing in that response is true, but it is exactly what I would expect to read in a summary about a plagiarism case, modeled off many newspaper articles about the same idea, I imagine. In the second, wherein I ask for evidence – a very different ask – the predictive model doesn’t have any, and it says so. (This is a big improvement over early ChatGPT, which would just make an answer up.)

This is a very long summary of the limitations of Generative AI, but I think it’s important to understand how the technology actually works in order to use it responsibly. You cannot expect the output to be truth: that’s not its job. But then, this isn’t a blog series about limitations, right? It’s about toxicity. So let’s get back to that.

So, What Is So Toxic About It?

I have so much to say about artificial intelligence that I am actually going to break this into two posts. Today I want to talk about the toxicity of how Generative AI handles the notion of intellectual property and the once-ubiquitous academic value of tracing the genesis of an idea. In my next post, I’m going to focus on equity and environmental issues.

Sarah Elaine Eaton, Canda’s foremost scholar on Academic Integrity, refers to the moment we are transitioning into as “postplagiarism.” I respect Sarah immensely and always have a lot of time for her work, but I bristle a bit at this particular neologism, because there is nothing post-plagiarism about the technology that underpins Generative AI’s content generation: it relies specifically on plagiarism, on regurgitating an idea without citing its original sources. In fact, citing sources is anathema to the entire functioning of ChatGPT and the ways in which it is designed to look and feel magical to the user. If anything, we are in a paraplagiarism moment: surrounded by a tool that questions the very issue of plagiarism as anything to be concerned about in the first place.

Why do we cite sources in the first place? Well, I guess I will go back to my English 101 writing class definition of the practice: citing our sources gives us an (often imperfect) opportunity to trace the genesis of our ideas and credit the people and texts that helped to shape them. It puts our ideas into context and adds our voices to an ongoing conversation. This has, traditionally, been a way that scholars demonstrate a core value of the academy: respecting the sources of ideas. This practice is not infallible, and citation pages have often been sites of racial exclusion and white supremacy.

But to abandon the practice entirely – and the speed with which so many academics have leapt to embrace a tool that functions in a way so counter to our shared core values – has surprised me. Sure, we all enjoyed a giggle when Generative AI spent its time generating false citations and trying to sound scholarly, but amazingly, we kept arguing for its place at the scholarly table. (I should note that ChatGPT rarely generates false citations now, and instead refuses to offer any citations at all. A user in that Reddit thread describes asking ChatGPT for citations as equivalent to “asking a vagabond on bath salts for directions” and, whew, I felt that in my chest.)

This is, by the way, also why ChatGPT is not a search engine. But hoo boy, try telling that to anyone.

I really do care about how ideas come to be, and tools like ChatGPT are designed to obfuscate. But even if I didn’t care about ideas and sources, I would still be annoyed that OpenAI has come to be a company valued at $29B with annual revenue of $1B on a dataset that it didn’t pay for and that it scraped without consent. We know for sure that the models were based on pirated copyrighted works including the corpus of the New York Times. How many of your ideas and sentences live within the OpenAI dataset already? You are not entitled to know that, apparently.

Can the large language models that ChatGPT and other Generative AI tools are based on even exist if they are forced to play within the bounds of copyright law? Probably not. So the final decision will be a social one: which construct do we value more? Intellectual property rights or Generative AI? And these are questions that will be decided in the courts, though recent lawsuits against OpenAI for copyright infringement seem to be struggling to find their footing.

And if you do dip into a tool like ChatGPT in the creation of your own research or writing output, what does that mean for your claims to ownership of the output? The truth is, we don’t know yet – and that, too, could have consequences down the road. But if you pay enough, OpenAI will incur your legal expenses if you get dinged for a copyright violation from using their tools.

That feels bleak as hell to me, but what do I know. Deep pockets trump moral clarity every time.

Strategies to Detoxify the Tool

I am not so foolish as to argue for a ban on any technology – not least because I fear the repercussions for students anytime we move towards a policing model. But I do wish we could slow down our adoption of this particular technology to have some frank conversations.

I don’t know if we can detoxify the intellectual property issue without the support of government policy and the resolution of court challenges , but here are some places to start.

- Disclose your use of AI. Not only in your research, where most journals require it, but in your teaching practice and with your learners. If it really is just a tool, and we’re really happy to make this shift in academic practice, transparency should be no big deal. Right? If disclosing AI use to students makes you uncomfortable, maybe that’s worth a deeper exploration.

- Please be mindful of feeding the beast. I see a lot of faculty feeding student work into supposed GPT-detectors, and all I can think about is the database that that material is going into (and also the potential violation of privacy laws). They also don’t work. I think, in general, we need to become much more suspicious of the aggregation of large amounts of text and other kinds of creation than we have been up to this point.

- We need to think critically about what we value in the creative realm. I am alarmed by how often I see writers who are critical of AI tools for writing turn around and use AI art generation for covers or advertising. This is a place where solidarity truly matters.

In my next post, we’re going to talk more about institutional values and how Generative AI perhaps shouldn’t find such a comfortable home within our universities. Does intellectual property as a concept still matter to us? What about things we put in our mission and values statements, like sustainability and equity? More on all of that next time.